African Symbolism Inquiry

History and ancestral knowledge as a vehicle for social and psychological development

Introduction

The goal of this document is to inquire on the meanings of symbols, motifs and patterns in Yoruba, Igbo and other African artifacts. The hope is that such inquiry, especially when done at scale, expands on the corpus of African history, mythology and ancestral knowledge. This broader project involves anthropology, semiotics and mythopoetics, to an ideal eventual end of integrative psycho-social development.

This is inspired by the idea that such artifacts serve to document history, and are not merely decorative objects. Such history, myths and stories provide moral and psychological lessons for individuals and society, in a way that’s deeply connected to particular cultures. This is especially pertinent in Africa where access to ancient art and knowledge of related semiotics is sparse, and in a world where there are clear but neglected psycho-spiritual roots to the many political and social problems.

The methodology for this inquiry relies on some speculation – especially in advance of connecting with cultural elders or researchers on such semiotics – but substantiates claims and interpretations through comparative analysis. This looks like identifying common symbols across cultures, and considering the possible narrative context of these interpretations. Comparative analysis at scale, potentially using AI techniques, might serve to place and strengthen interpretation of the semiotic corpus, as well as validate speculative or other anecdotal data. An implicit desire here is to utilize the breadth of existing digitized excavations to hypothesize on African history, alongside/in advance of in-situ archeological inquiry.

Paths of Inquiry

To approach this inquiry, we investigate certain speculative, comparative and established semiotics. In such a broad project, we present these few concrete paths to look into:

Symbolism possibly indicating numerics: weave patterns and other repetitive elements, shown on Yoruba artifacts with known ritual context (carved panels and Ifa divination boards)

Narrative pictographic symbols and motifs: animal symbols like ouroboros/snake-eating-it’s-tail (symbolizing reincarnation/rebirth), birds/doves (symbolizing peace), alligators (symbolizing war or justice), and monkeys (symbolizing naive instinctual nature). These are also common on door panels and textiles

Established translations of symbol systems and translations: Nsibidi has documented translations by early anthropologists, and talismanic tunics with Arabic (Ajami) script alongside symbols/motifs could also serve as “Rosetta stone”s

These paths are interrelated, and go from (respectively):

Speculatively interpreting more abstract symbols, to

Drawing narratives from pictographic symbols and motifs, based on comparative knowledge from other cultures, to

Reflecting on existing translations of similar and closely (geographically) related symbol systems

Now let’s explore each of these paths, analyzing a set of artifacts and coming to informed conclusions about them.

Symbolism Indicating Numerics

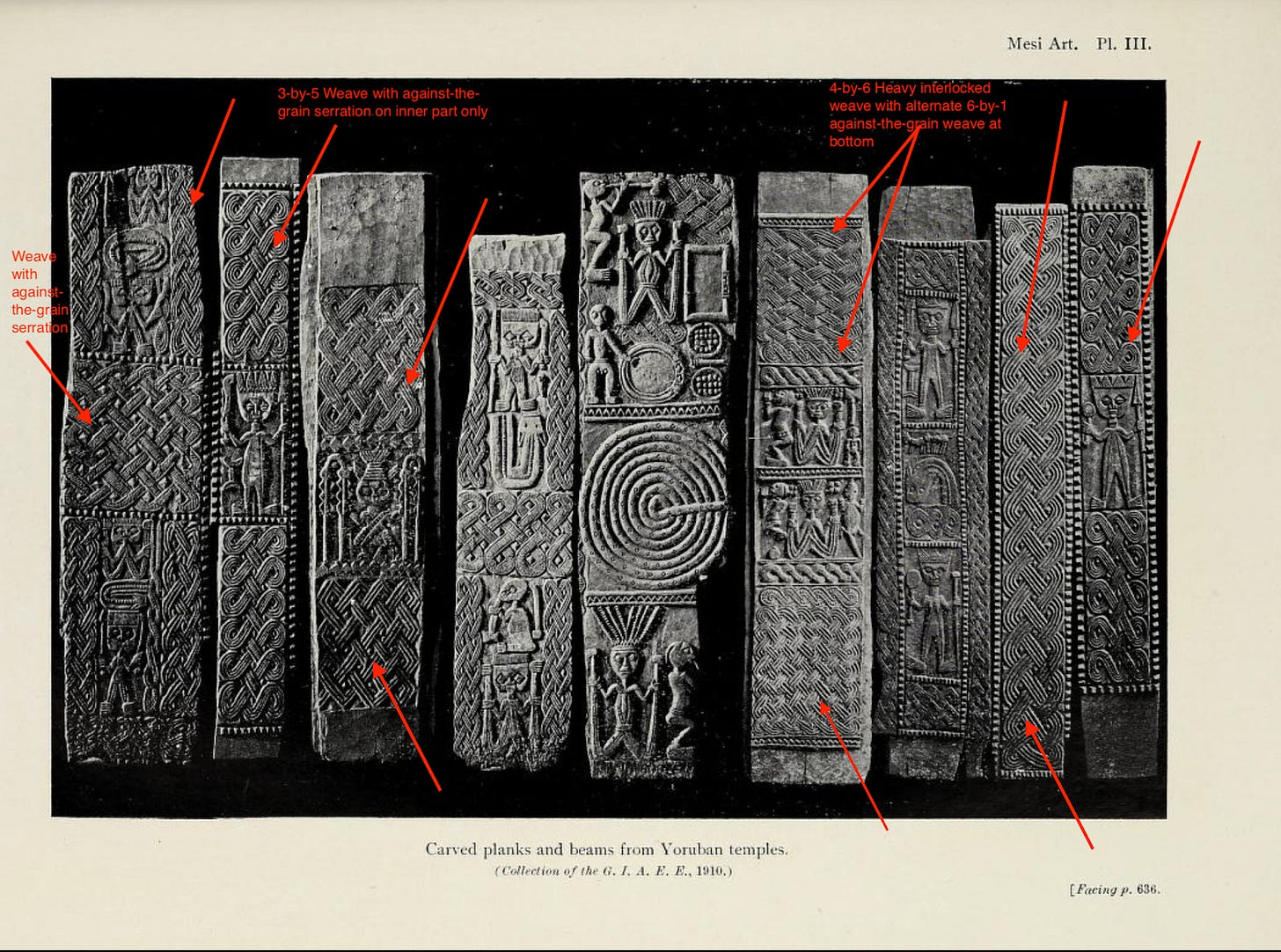

Weave patterns show up prominently in Yoruba door panels and textiles, these would seem to refer to numerics based on counting the intersections. Additionally, various levels of detail exist that might indicate higher-order numbers, including inner lines/serrations in the weave which might be with- or against-the-grain. These numeric indicators adapt to context, representing things like numberings for verses used in Ifa divination, or potentially the passage of time in narrative pictographs.

Analysis

For the following images of artifacts, we attempt to determine what numbers the weave patterns represent by counting the row- and column-wise knots, which include variations such that they add up to odd or even numbers. This method of counting is shown in several examples in the images below, where we can ground/confirm the interpreted numbers based on the context of the artifacts.

The image below of “Carved planks and beams from Yoruba temples” from Leo Frobenius’ 1910 archeological expedition, shows a few different weave patterns in a (potentially ordered) sequence of panels. These might appear to symbolize a numeric/quantified passage of time in a narrative of royal succession driven by the pictorial symbols – more on the pictographs and the corresponding narrative in the next section Narratives and Associations of Pictographic Symbols

Figure 1: Carved planks and beams from Yoruba temples. Source: Frobenius’ expedition to Nigeria, German Inner African Exploration Expedition in the years 1910-1912 https://archive.org/details/voiceofafricabei02frob/page/634/mode/2up . (annotated)

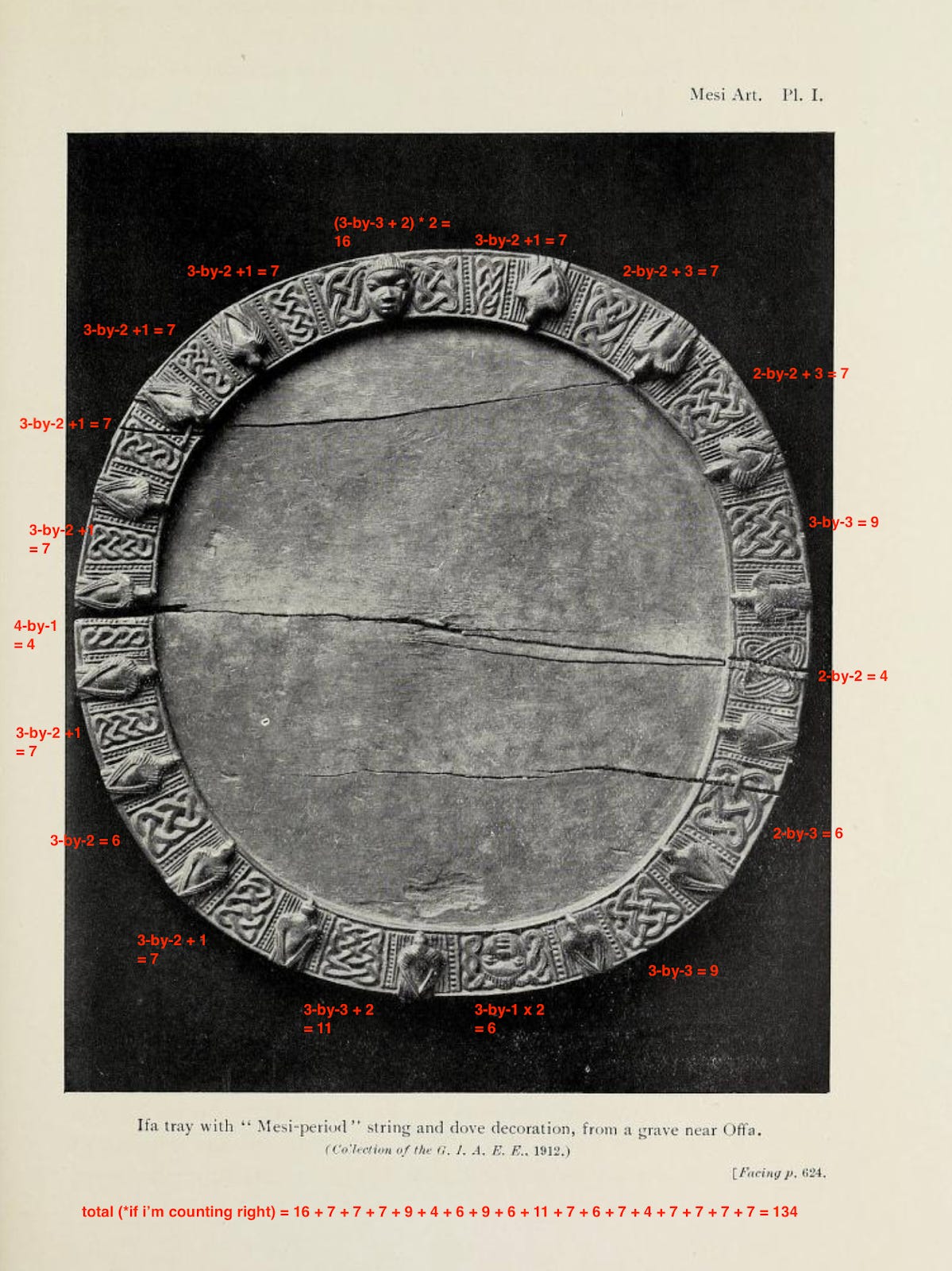

As another example of these numeric symbols, there are some instances of these showing up on Ifa divination boards, where such weaved patterns likely mark how the 16 major or 256 overall Odu Ifa scriptures may be interpreted. Without going into specific of interpreting this (which I am not qualified nor initiated to do), here’s 2 examples of boards that use this similar weave-based numeric symbolism

This other example shows an Ifa divination tray circa 2008, with 3 of these woven patterns which, when counted by knots, sums up to 16!

Figure 2: Ikin Orossi game. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Jogo_de_Ikin_Orossi.JPG. (annotated)

Another example Ifa divination tray circa 1912, from the same aforementioned Frobenius expedition, shows a number of these patterns. A rough count gets us to a number that’s about 256/2, where 256 is the total number of Odu Ifa verses - The count is rough because it’s not totally clear how to count all the sets of weaves, which are 16, excluding the 2 “polar” face representations flanked with weave patterns

Figure 3: Ifa tray with “Mesi-period” string and dove donations, from a grave near Offa. Source: Frobenius’ expedition to Nigeria, German Inner African Exploration Expedition in the years 1910-1912 https://archive.org/details/voiceofafricabei02frob. (annotated)

Conclusion

There seems to be some strong link between the woven patterns and numerics, basing this upon the known numerics used in Ifa divination. Additionally we may speculate on what purpose such numeric representations serve in the pictographic door panels, likely representing the passage of time – This could be corroborated by aligning the narratives representing oral histories, which the next section focuses on, and comparatively analyzing with visually similar systems like Lusona.

Narratives and Associations of Pictographic Symbols

Narrative pictographs are present on much Yoruba, Benin and Igbo art, in the form of carvings on sculptures, panels, and many other practical and ritual instruments – the Benin plaques are a notorious example of such, representing the lineage of Ogisos and Obas in alignment with oral history. The motifs of such pictographs have many commonalities and can be generally assumed to have some narrative structure. Expanding on prior knowledge, and interpreting such narratives at scale, is a compelling direct path towards expanded “literal” corpus of African history. This is especially compelling considering the speculation on numeric symbols and such representations, which could bolster oral histories with precise or detailed information like the relative timing of events or quantities of people or things.

Analysis

There is a dedicated article that does a detailed narrative analysis of “Figure 1: Carved planks and beams from Yoruba temples” here: On Yoruba Art as Historic Storytelling: Carved planks and beams from Yoruba temples - a narrative and symbolic analysis

Conclusion

As shown in the above article, an initial speculative interpretation yields coherent and promising narrative understandings that’s fairly detailed. Expanding this to a larger corpus of carved panels — specifically authentic panels from archaic periods, such as this one — is likely to uncover much more narrative detail. In fact, such detailed interpretations could serve as “training data” for automated analysis. Additionally, corroborating such analysis with oral tradition provides good grounding for any speculation – further still, comparative cross-cultural analysis of symbolic and mythology forms might reveal more dimensions to our interrelated histories, mythopoetics and cultural psyches.

Established Translations of Symbol Systems

Modern writing systems often have ancestry in earlier pictographic symbol systems. These knowledge systems come about in organized societal processes, and the move from pictorial to abstract is considered to be due to standardization and broadening literacy. African symbol systems exist across this spectrum, which might reflect either the relative development of organized knowledge/literature systems, or the modern connection to or awareness of potential lost systems. It is worthwhile to speculate/investigate the latter, given the relative archeological under-excavation in Africa and the “dark ages” exemplified by the slave trade – a period which, like Europe’s dark ages, represented a stagnation/regression in knowledge (perhaps outside of monasteries).

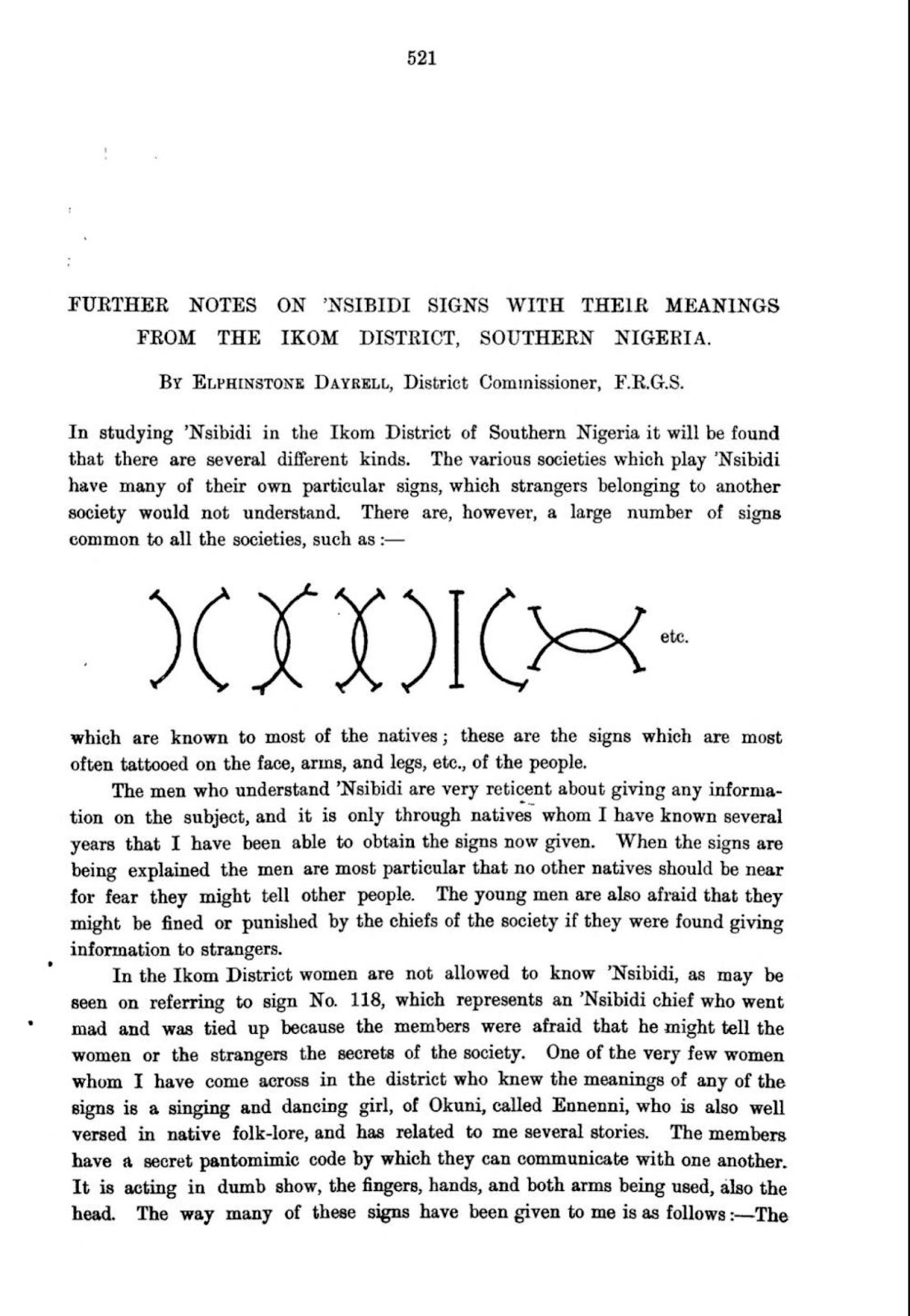

Moving on from the speculative approach of the previous sections, this section will highlight established ancient symbol systems in Africa, the most notable and well documented of these being Nsibidi. This system of symbols is dated broadly between the 5th and 15th centuries (notably aligning with the dating around Igbo-Ukwu art from the 9th century). In terms of the purpose of the system, it served as general knowledge including in schools, but also included sacred symbols that are kept secret. The nature of the symbols is mostly abstract and represent certain entities, and are combined together for more meaning - referring to everything from human relationships and court proceedings to architecture and household objects

Analysis

This analysis will summarize a particular reference on Nsibidi symbols and meanings, from the chapter “Further Notes on Nsibidi Signs with their Meanings from the Ikom District, Southern Nigeria” in Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, Vol. XLI, 1911. Pages 521-540, which is fully available online here: https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.537265/page/n683/mode/1up.

Here’s some key observations about these symbols based on this account of attaining their interpretations:

These meanings existed, as at the early 20th century, heavily among local elders or initiates of secret societies who are usually men.

The visual language is accompanied by a means of bodily communication with subtle movements, perhaps for the sake of secrecy among initiates (see page 523)

The symbols also exist in art, bodily tattoos notably, though maybe not with known meanings by the wider public (see page 522)

There are regional collections of symbols, shown by the archeologist visiting various locals (see page 522)

The symbols vary in representation but are often similar or interrelated, including many abstract forms and some more apparently pictographic. (see page 523)

The symbols serve a narrative purpose that is closely related to the mythology of Igbo culture

Figure 4: Chapter introduction to “Further Notes on Nsibidi Signs with their Meanings from the Ikom District, Southern Nigeria”. Source: https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.537265/page/n683/mode/1up

Conclusion

Nsibidi as a system of symbols presents many of the characteristics identified above in terms of abstract and pictorial forms, narrative structure, and the socialization of knowledge about them. In terms of societal knowledge, in recent times it appears more closed off from the general populace which doesn’t seem to have always been the case through its long history. This report from Elphinstone Dayrell on the meanings is a crucial resource, alongside knowledge that remains among elders, experts, as well as that which can be gleaned from excavated artifacts. Here again, large-scale comparative analysis and categorization of such symbols and how they are used may serve to extend the corpus of myths and practices they present, as well as inform other ways of individual and collective societal development today.

Epilogue

In the spirit of narrative writing, this sequence of inquiries into a set of African symbolic systems serves to inspire more such research. Specifically, the hopeful follow-on work and outcomes of such work are:

Collation of photographs of various artifacts that display such symbolic forms, with context on their origin and purpose

Large-scale comparative analysis of the symbolic forms displayed on such artifacts, given the necessary context, leading to more or corroborated histories, narratives and myths from African culture. This corroboration adding another level of detail to oral traditions

Synthesis of relevant themes in African mythology and history aimed to address relevant problems today. Some imagined examples might include narratives speaking to youth issues, land management, trade and production, justice and moral codes e.t.c.

Altogether, this inquiry presents promising paths forward in research on African history, anthropology and psychology, hopefully leading to concrete recommendations or programs towards more holistic development – representing a Sankofa “looking back” at our past, the sparking of a renaissance, and a new light to shed away Africa’s “dark age” of the past few centuries.